SmartUp Project: Preliminary lessons and provocations for design, operation and policy making of smart homes

SmartUp Project: Preliminary lessons and provocations for design, operation and policy making of smart homes

This article explores preliminary findings on what happens to homes when they become smarter, considering how going digital affects the ways in which homes are imagined, planned, designed, and experienced on an everyday basis, provoking decision-makers to think widely about the contexts and consequences of their actions when implementing smart technologies to improve building performance.

Authors

Clarice Bleil de Souza, Full Professor, Welsh School of Architecture - Cardiff University, UK

Personal profile | LinkedIn profile

Blanka Nyklova, Research Fellow, Institute of Sociology, Czech Academy of Sciences, Czech Republic

Personal profile | LinkedIn profile

Dorota Golanska, Associate Professor, Department of Cultural Research, University of Lodz, Poland

Julia Gruhlich, Postdoctoral Researcher, Diversity Research Institute, Göttingen University, Germany

Personal profile | LinkedIn profile

Nils Ehrenberg, Postdoctoral Researcher, Department of Design, Aalto University, Finland

Personal profile | LinkedIn profile

Bartosz Hamarowski, PhD Student, Doctoral School of Humanities, Theology and Arts - Nicolaus Copernicus University, Poland

Sandra Frydrysiak, Assistant Professor, Department of Cultural Research, University of Lodz, Poland & SWPS University in Warsaw, Poland

Anna Badyina, Research Associate, Welsh School of Architecture - Cardiff University, UK

Personal profile | LinkedIn profile

(Note: opinions in the articles are of the authors only and do not necessarily reflect the opinion of the EU).

Introduction

Trends in home automation and the increasing use of digital technologies for diverse purposes-such as management of comfort, energy efficiency, security, surveillance, maintenance, care provision, health supervision, entertainment, education, and work - have led to the emergence of what is referred to as a connected, networked, augmented, intelligent, or smart home (1, 2) . However, the increasing role of software and mobile technology in everyday life calls for expanding the notion of smart home from a sole focus on appliances and integrated systems inside the dwelling to encompass both the different lifestyles of individual residents of smart homes and broader social and systemic contexts in which they are situated (3, 4).

Technologisation and digitalisation have a substantial potential to challenge established household routines, dislocate usual equilibriums of work and care or work and leisure, and promote new markets out of which different types of service provisions and social interactions emerge. Smart homes function as human-technology interfaces and tend to be designed as ‘resident-’ or ’owner-centric’ as well as ‘user-friendly’.

However, as an element of wider infrastructures of cities or (smart) grids, imagined as potentially transforming everyday life not only locally but also globally, smart homes are part of more general economic, cultural, and social forces, which shape them and are shaped by them in return. Understanding the context and impact of technical decisions in designing and managing ‘smart homes’ and identifying the socio-cultural, political, institutional, and regulatory factors, perception and values that influence these activities and outcomes are of particular importance to professionals involved in smart home design and operation, and those developing policies related to the implementation of smart buildings. It would be advisable for them to critically engage with the situation within which professionals have to practice and identify the key drivers, barriers, and potentials in dealing with issues of accessibility, equality, control, and privacy of the home as well as understand barriers and potentials related to technology implementation, adoption and appropriation by homeowners and tenants.

The Smart Up project

The project Smart(ening up the modern) home: Redesigning power dynamics through domestic space digitalisation (SMARTUP) examines ‘smart home’ initiatives across different socio-cultural contexts, looking at their impacts on the realities of everyday life, policy, and professional practice, including how these initiatives contribute to redesigning the dominant social power dynamics.

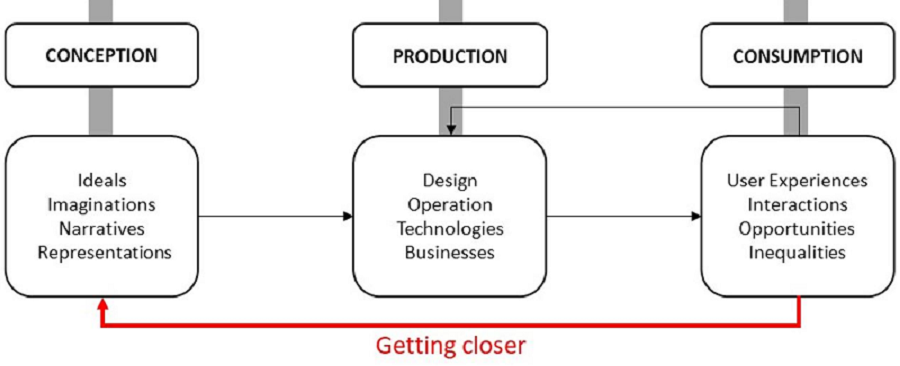

SMARTUP draws on insights from several academic disciplines situated at the overlap of social sciences, arts, and humanities, integrating theoretical and methodological approaches originating within home studies, gender studies, science and technology, design studies, and posthuman theory. Using a human-centric and system of systems approach (Figure 1), it examines smart homes’ CONCEPTION (i.e., home as an idea and ideal); PRODUCTION (i.e., home as a matter of design and planning), and CONSUMPTION (i.e., home as practiced, lived, and experienced). By reconciling interdisciplinary perspectives, as well as views from different European countries across Central/Eastern (CZ, PL), Western (GB, GE), and Northern (FIN) Europe, SMARTUP showcases problems from a variety of approaches, providing potential arguments for stakeholders to negotiate and co-develop smart home solutions that go beyond the efficiency-oriented paradigm.

This article specifically focuses on discussions, situations and events, use-cases, impact, and consequences of decisions related to implementing smart technologies to improve building performance. It attempts to raise awareness to decision-makers that their decisions go beyond their assigned tasks and responsibilities; changing human-human interactions and lifestyles inside the home as well as what the home can now afford, including expectations on what homes are now supposed to provide.

Figure 1 – The SmartUp project overview

Market responses and the production of innovative lifestyles

Market responses include full reinventions of the home, deploying environments which are now supposed to provide ‘comprehensive’ lived experiences, in which the space is a ‘stage’ for different types of interactions to be commercialised and managed by smart systems (9). These experiences include ‘comprehensive smart tenancy agreements’ which go from offering an ‘all-included’ tenancy bill (containing all utility services within it) up to activities for the weekends as well as packages of social life, along with common spaces for socialising as well as working. This kind of package offering opens questions to how smart housing will transform the configuration of the home, and by extension the city around it. While these kinds of new housing solutions are emerging, and offering developers new tools for operating and maintaining their housing stock, it is also important to consider that the new housing solutions:

- Provide new blueprints for what a home is or can be,

- Standardise asset management towards the delivery of specific conditions inside building spaces, matching comprehensive packages of experiences a building is now intended to deliver, and

- Promote the ‘flexibilisation’ of performance assessment to include how clients want end-users to use a building.

When providing blueprint of what a building can be, market responses change types of activities inside buildings, changing the understanding of what is public and what is private, consequently changing the needs and types of interfaces for occupants to interact with buildings as well as building internal configurations. These include the delivery of specific types of indoor environmental qualities, changing performance assessment criteria related towards them. For instance, co-living, comprehensive and collective living experiences, transforming the meaning of the home by constraining tenants to live in private spaces which are essentially fulfilling the functions of sleeping, daily hygiene and resting.

Living, dining, and cooking activities associated with the ‘traditional’ home are now collectively happening in shared spaces heavily regulated by building facility management rules which also control the delivery of comfort and indoor air quality conditions, including music and lighting in some of these spaces. Asset management is geared to the delivery of specific ambiences to activities which are supposed to be undertaken collectively persuading end-users to behave in specific ways through the type of music, lighting and temperatures provided. End-user control of indoor environmental qualities is restricted to their private spaces while at the same time heavily monitored in relation to fulfilling asset management objectives. Tenants pay for an ‘all-included’ rent, in which energy bills are included. Therefore, they are monitored and warned on their energy expenditure towards fitting within pre-specified building operation management ranges.

In these heavily constrained, regulated, and controlled homes there is no nurturing or making people connect to the spaces they live in. All is taken care for them, a change in lifestyle that dramatically impacts on our everyday life as well as on the relationships we develop with the buildings we live in. While these smart co-living solutions claim to offer/provide all the comforts of modern life with more flexible and comprehensive contracts, they also have implications for the autonomy of the tenants. Technologies in these buildings do not only offer landlords additional tools for managing and maintaining their buildings but also for shaping what kind of lifestyle the tenants should maintain, transforming the residence from a home to a commodity.

Unconsciously designing power relations

Examples like co-living clearly show that design decisions, from conception to materialisation, shape and are shaped by power relations between the different stakeholders involved in the design process. Why is the design of unconscious power relations important to professionals involved in building design and operation? Mapping and understanding power relations enables us to assess how smart technologies enhance, diminish, or completely shift ownership, control, and decision-making in design and operation. Key aspects include:

- The commodification of the home, raising issues related to maintenance and liabilities associated to who should have agency over care,

- The servitisation of building systems and components, creating overlaps and nested ownerships in Rights to Property which are difficult to resolve,

- The creation of new demands in relation to control, afforded by extensive intrusion which resemble dystopian scenarios of private spaces, and

- Power is softly mediated in the implementation of ‘smart home’ initiatives, through professionals’ perspectives on everyday life of residents and context and conditions of their professional practice. Yet, the implementation (practice) domain is rarely critically scrutinised by professionals who do not often understand why their plan is not achieved or leads to poor results.

When delivering ‘smart life experiences’ the market promotes the commodification of the home. Understanding homes as a commodity can easily result in end-user alienation and passive attitudes to care due to loss of affordances, raising questions about what end-users’ real responsibilities are. This is particularly the case when the home is stripped into a set of different services delivered by third parties providing ‘comprehensive contracts’ which include product, installation, maintenance, and end of life disposal. While they seem to provide an affordable solution to the promotion of energy efficient products and offer the convenience of being repaired and replaced when needed, they depend on end-users understanding how to effectively use the service. In addition, while, for instance the servitisation of building energy systems can be offered as an affordable solution to energy transition (e.g., leasehold packages of heat pumps and renewable energy generation and storage), it complicates building owners Rights to Property. As leasehold heating packages need to be bought by homeowners, transferred to a new property, or removed if the house is sold, they might be increasing home EPC ratings but can devaluate assets by dispossessing owners from having full Rights to Property.

Smart systems, when implemented to promote energy efficiency, can also create new tensions between stakeholders afforded by extensive intrusion. For instance, in some types of tenancy agreements (e.g., government provided social housing), landlords can see detailed energy profile of tenants and therefore sue them for not heating the house enough to prevent condensation and mould growth bringing issues related to liabilities and responsibilities associated to care and maintenance to the fore. Affordances of this type reinforce and increase mistrust, negatively affecting delicate balances in the relationship between landlords and tenants while at the same time disengaging citizens from collaborating with initiatives related to smart energy efficiency.

Unintended consequences & impact in everyday life

The way in which smart homes technologies such as digitalised household appliances, energy, and security technologies are controlled, either by digital agents or not, affects the way household members perceive control and how their use is negotiated in relation to family division of labour, home, and childcare responsibilities, etc. These not only affect assumptions about building occupancy in space and time impacting on design and operation but expose important consequences of design and operation decisions in intimate aspects of our lives, such as for instance:

- Producing new dependency relationships inside families and changing social dynamics inside the house,

- Requiring time commitment through continuous engagement to deliver what is promised, and

- Creating new affordances not imagined before in the microcosmos of the home.

SmartUp attempts to map what these unintended consequences and impacts are so professionals involved in building design and operation can also understand the impact of their decisions on the microcosmos of the home. We did observe that while smartisation potentially give a lot more control to men inside families, (e.g., overview of energy efficiency and controlling energy consumption (e.g. time and length of showering) or even their partner's social encounter), the digitalisation of previously female-implied household chores is seen to encourage men to do more work in the household (e.g., men who program the robot hoover and take responsibility for cleaning the floor). However, engagement with smart technologies requires time, to understand interfaces, operation patters, learn how to input control settings, etc. let alone being on top of it for software updates with new features related to security, new functionalities, etc. In most cases, it is also the men who are responsible for this digital housekeeping (10), which can mean that they tend to withdraw from social interaction in the home in order to work out the technology. This, therefore, contradicts the selling points related to producing efficiencies, at least efficiencies related to convenience and time management.

End-user engagement is important, if not fundamental, to understand how to use the service so any design or operation goal is properly achieved. Counter examples can span from not knowing how to interact with a product interface up to using a product for a purpose not initially intended depending on how technology savvy the end user is as well as his/her cultural background, age, etc. (e.g., social housing elderly tenant who set fire to her own house after leaving an aluminum pan in her smart cooker, assuming it was off as there was no flame). Imagined affordances, like the example with the saucepan, need to be understood to prevent serious accidents, whereas new affordances need to be carefully understood such as surveillance among family members, (e.g., parents remotely switching the hot water off after seeing how long their children stay in the shower), as they potentially reinforce existing inequalities and/or create new ones.

Conclusions: Co-designing a smart future

Far from exhaustive, these preliminary results are supposed to work as a combination of provocation, eye-opening and information to those involved in building design, operation and policymaking. They show the importance of thinking outside disciplinary silos and bringing professionals together to co-reflect on their practice to learn lessons to foster better outcomes and open new possibilities in ‘smart home’ (11). They depict preliminary results of what happens when we adopt a human-centric and system of systems approach, expanding from design, operation and policy making towards including insightful criticism from the Social Sciences, arts and Humanities.

Starting by cataloguing lessons learned up to pointing out where inequalities and injustices are likely to occur, Social Scientists have an intellectual arsenal to understand and help mediate the implications of design practice. Much is still to be done with regards to negotiating knowledge from the arts, humanities and social sciences towards producing a more reductionistic approach for systemic implementation. However, expanding the scope of analysis and understanding the implications of how decisions are translated into, and interwoven with, stakeholders’ needs and lived experiences of end-users can be a promising starting point of departure to develop more informed solutions that effectively contribute to address the grand challenges and build resilient communities while more truly fulfilling end-users needs.

References

(1) Clements-Croome, D. ed 2006. Creating the productive workplace. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis, 2nd Edition.

(2) de Wilde, P. 2018. Building performance analysis. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

(3) Vargo, S.L. & Lusch, R.F. (2004) Evolving to a New Dominant Logic for Marketing, Journal of Marketing, 68(1), 1–17.

(4) Kitchin, R. & Dodge, M. 2011. Code/Space: Software and Everyday Life. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

(5) HomeForest (Squint/Opera, Haptic Architects, Coda to Coda, LionHeart, Yaoyao Meng). (2021). HomeForest [Desing Project]. Available at: https://thedavidsonprize.com/awards/2021/home-forest-longlist

(6) Mann, Alex. (2018). Cool [Film]. Space Odity Films. Available at: https://www.spaceoddity.xyz/films

(7) Jeunet, Jean-Pierre. (2022). BigBug [Film]. Eskwad / Gaumont.

(8) Ocean Builders (2022). SeaPod. Oceanfront Living [Promotional Material]. Available at: https://oceanbuilders.com/seapod/.

(9) Ehrenberg, N., Keinonen, T. Co-living as a rental home experience: Smart Home technologies and autonomy. Interaction Design and Architecture(s) Journal – IxD&A, n. 50, 2021. Pp 82-101.

(10) Strengers, Y.; Kennedy, J. (2020): The Smart Wife: Why Siri, Alexa, and Other Smart Home Devices Need a Feminist Reboot. Cambridge: MIT Press.

(11) Schon, D.A. (1983) The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. Basic Books, New York.