Is circularity really accessible to all society?

Is circularity really accessible to all society?

When taking into consideration poor areas and society, we see that circularity principles are not easily implemented, nor easily understood by people. Indeed, as part of what the Houseful project is doing, there is the need to face the problem in a different perspective, such as, for example, focusing on how much energy would be saved if circularity was applied.

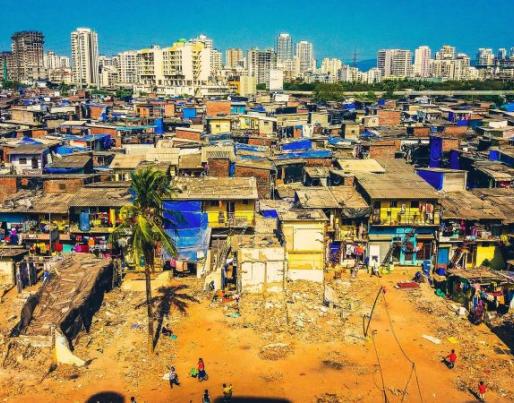

"There is a real risk of circularity becoming a privilege for the rich,” warns Chris Patermann, father of the bioeconomy. In Spain and Italy, two projects are testing new solutions to tear down the barriers hindering the uptake of a sustainable approach and fostering social inclusion in poor areas.

Figures by the French Statistics Institute, INSEE, show that in 2016, 78 million EU citizens were unable to meet basic needs such as replacing two pairs of properly fitting shoes or worn-out clothes. It is what experts call “material or social deprivation”, a condition common to 15% of European citizens. “A circular approach on a large scale will never be possible unless we involve these people in sustainable practices too”, says Beatriz Medina, an environmental and social scientist at the consulting company We&B. “It would be like building a roof but forgetting the house underneath”. Within Houseful, an EU-funded project aimed at proposing circular solutions and services for the housing sector, Medina works at bringing them to “difficult” settings such as poor neighborhoods, home to families with social vulnerabilities.

When circularity is not a priority

One of the demonstration sites where such an innovative approach is being tested is in Campoamor, a working-class district in Sabadell, a town in the outskirts of Barcelona. The district arose as a result of internal migrations mainly from Andalucía, but when this first wave of residents left, they were mainly replaced by migrants from other countries.

“The unemployment rate is very high. Most of the people have quite low incomes and especially among migrants there a lot of large families needing social assistance”, says Montserrat Muniente, president of a local neighborhood association, bringing together 800 families. “If I suggested they put solar PV on their roofs, they would think I was crazy. A few of them are owners, most are renting and some are squatters. Their situations are too different and whenever there is something to pay, it becomes impossible to get everyone to agree”.

“The circularity of the building they live in ranks quite low in their priorities. What these people need is first of all affordable rent, a job, and a good education for their children”, says Dara Turnbull, research coordinator at Housing Europe. “When we talk to them, rather than focusing on sustainability, we have to explain to them the practical impact of such solutions on their everyday life: how much they will save on their heating or electricity bills, how much comfort they will gain in their apartments, etc”.

Housing Europe is a network of 46 national and regional federations, gathering 43,000 public, social, and cooperative housing providers in 25 countries. Its role within the Houseful Project is primarily to collect the feedback on the ground, to understand what problems might have arisen, and in doing so, to pave the way for replicating the solutions tested. “After working on four demonstration sites, we’ve now identified the first of ten ‘follower buildings’, which will replicate them in turn. Each of them will then hopefully find ten more followers and so our model will grow exponentially”.

Read the full article here.